At Marylene’s

By LeeAnn Perry

October 15, 2023

October 15, 2023

Thirty-eight hours after catching the person I expected to spend the rest of my life with on Tinder, I was on a plane to LA, to Marylene’s.

Marylene and I had met in June, sometime between midnight and six AM in a Berlin techno club. Nick knew her boyfriend Andrew from Brooklyn, and as they caught up we connected over our love of music, from Stravinsky to musique concrète to Delta blues. Marylene was wearing a sheer black shirt and dark eyeliner. She spoke with an emphatic French cadence, smoked Gauloises with casual grace, and wore her blonde hair long and slightly tangled. We had both just taken acid, I for the first time.

My relationship with Nick was new, and I was new to his world, the world of psychedelics and art and money, of Bushwick warehouse raves and summer techno pilgrimages to Berlin. I still carried both the moldy vulgarity of my West Virginian upbringing and a deep sense of my own misshapenness from growing up non-white and isolated by homeschool. I was afraid to open my mouth around his friends, afraid of being too sure of my own opinions, but as I talked to Marylene and the acid began its work I let myself think I could belong. In the haze and pounding bass, I imagined infinite pathways branching out from that moment, each transforming me into a different and glittering self: a musician, a writer, an artist, thin and sophisticated and worthy of love.

Perhaps that was why, over the next few months, I missed the signs that things weren’t working out with Nick. I had little experience with relationships, and had thought the tumultuous course of our four-month relationship might continue just as it was. I had thought, with no evidence, that he and I were both going to swallow our doubt and restlessness, and move in together in two days when my latest sublet, a flea-infested San Francisco apartment I shared with two DJs and a coke dealer, was over. When we broke up I had nowhere to go, no plans for the future, no school or employment to anchor me. I peddled my tragedy of abandonment on social media, looking for friends willing to store my belongings or provide a place to crash, no small sacrifice in a city where no one I knew could afford a living room. There, I saw Marylene’s post in search of a cat sitter.

We’d only met once, but I’d seen enough of her life on social media to envy her. She was a fashion photographer, and I had acne. She owned a black ‘77 Firebird, and I had never learned to drive. She toured with Japanese psych-rock bands, and I had only ever been a face in the crowd. She was a connection to Nick, and I was an episode in his past.

The next day, I cried on BART, the plane, the airport shuttle. By the time I arrived at the Villa Elaine apartments in Hollywood, I was dehydrated and dissociated. A four digit code took me through the black iron gates and into a courtyard with stone fountains and banana palms. It felt surreal: the colors too bright, the edges of things too sharp, the stillness and quiet and lushness too hermetic. Marylene’s neighbor Joyce gave me the keys, pointed out the units where Man Ray, Orson Welles, and Frank Sinatra once lived. She invited me over for tea sometime. Her warmth overwhelmed me; I made my excuses quickly and retreated.

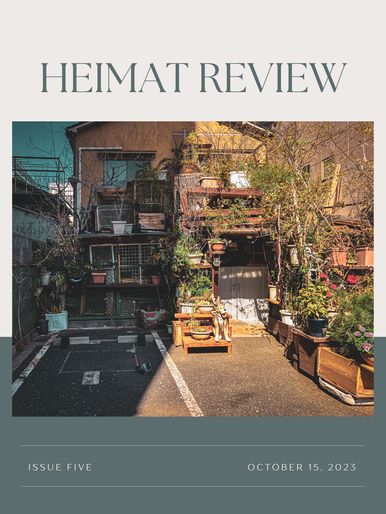

Marylene’s loft had high ceilings and dark red floors. The cavernous atrium held a couch, a piano, and a shelf with synthesizers and a skull. Small steps led to a spare kitchen, which opened into a vertiginously long and narrow alleyway crammed with potted succulents and cigarette butts. A winding staircase led up into an alcove with a modest bed and bath. The cats, Grey and Glenn, followed me from room to room but kept a polite distance.

It felt like an interstitial place, a place disconnected from the narrative of my life thus far, from the world I knew, from my habits and comforts; any pain brought into it would remain frozen in time, unable to change or leave. I drew layers of gauzy curtains across the floor-length picture windows and locked myself in. I didn’t know it was possible to feel so alone.

On that first night, I unpacked. I had brought only a few changes of clothing, a tarot deck, my journal, and 20 hits of acid. I fed Marylene’s cats and picked at the food in Marylene’s fridge and lay restlessly in Marylene’s bed until it began to get light outside. I stayed in bed while the midday sun pierced through the curtains with angry heat. Faintly, I heard life outside continuing, and it seemed healthy and bright and horrible: fragments of Top 40 music from cars driving down Vine, fragments of conversation from people walking by, always fragments moving past me in my stillness. I wondered which side of the bed Marylene slept on, if she got up early or late, if Nick was in love with her, if she had a middle name. Eventually, it started to get dark again. I stayed in bed.

When I woke up again, I had become a non-being, existing only in the space left by the absence of a woman I barely knew. I sat in the bathtub and sampled the deep ambers of Marylene’s perfumes. I touched the austere white silk hanging in her closet and wondered if anything that elegant could work on me. As I folded and put away the clothes she’d left in the dryer I noted the brands, imagined wearing them, looking beautiful in them, being desired in them.

I fed her cats with precise scoops twice a day and played with them seriously and assiduously. I looked through her records, but didn’t listen to any because I was afraid to touch her intimidating mixer, afraid I’d damage her speakers by powering things on in the wrong order or plugging something in the wrong way. I didn’t play her piano because I didn’t want anyone to hear me. I put things back carefully when I used them.

One night I went outside. I walked to Sunset Boulevard to buy the toiletries I’d forgotten to pack, and came back with a box of nitrous and a bottle of wine. I finished both, watching the dark walls melt and breathe, watching skulls swim in and out of darkness. Inertia expanded inside me like nitrous, carrying blue numbness to my brain, to my heart, to the tips of my fingers. The next night I finished another box of nitrous and another bottle of wine. The next night, it became routine. In those seconds after a hit of nitrous I could plausibly conjure grandiose visions of reconciliation, forgiveness, and commitment. Sober, there was only an erased tape where once I had played and replayed my future with Nick: reading the books he liked, meeting the friends he talked about, DJing together in crowded Brooklyn warehouses and sweaty Berlin clubs.

Marylene texted me to check in, and met my honesty with her own. She’d flown to Brooklyn to save her relationship with Andrew, but she said everything she tried made it seem to fall apart faster. I blended her words with mine and wrote them in my journal. How can something become nothing? Where does the potential go? What happens to the space where it once was? I had no wisdom or reassurance to share, so I sent photographs of her cats, of shadows on the floor, of a tongue of cigarette smoke curling upward in still air, trying to prove to her in an oblique visual language that she had been heard and understood. I knew little of Marylene’s personality, her behavior, the way she moved through the world, but I knew our pain oscillated at the same frequency; we resonated.

Marylene was the only person I was in regular contact with. I went out only at night to buy supplies, and when I talked to the cats my voice was whispery with disuse. When the cashier at the nitrous shop told me I should be taking B vitamins to prevent nerve damage, I started going somewhere else. When Joyce knocked, I hid from her. I watched as texts from worried friends in San Francisco piled up, then as my phone rang and rang and rang. Instead of reaching out, I gave the cats tarot readings. I went through the deck and picked out the swords, explaining exactly what flavor of pain each embodies, and then I pulled cards to represent what in their lives was hurting. The ten of cups suggests you are unhappy because you avoid connection, the Sun here indicates your lack of successes in life. They walked across the spread to come twine themselves around me with what I couldn’t convince myself was real affection.

Something like a week passed, but time did not find me in Marylene’s apartment: the fruit I bought had not ripened, the emails I tried to write went unsent, and my pain had not diminished or shifted. One night I took the acid, trying to remember what it was like to feel the raw manifold potential of life. Instead, I felt I had lost control over my one bleak and clouded fate. My journaling shifted to third person. I wrote demonically, as if everything I had ever seen or thought became sentient and fought to escape my dying body. I became certain I would take my own life, without even wanting to, because I didn’t know where, or how, I was going to live after this. I could see no future beyond my stay at Marylene’s.

I drafted notes to Marylene, to explain myself: “Thank you for letting me stay in your beautiful home. The cats have been fed once today. My body is in the bedroom…” I wondered if Marylene ever sat at the kitchen table, smoking and waiting to die. If even someone like Marylene couldn’t find bliss in love, then what hope was there for me?

One night Marylene texted that she and Andrew were over. I turned out all the lights and texted back a picture of the unbroken darkness. She promised that I could stay as long as I needed to.

I imagined that Marylene came back and I gave her my journal to read. We put lit candles on every flat surface and sat on the floor with the cats in a circle of salt and ash and cast a spell to dissolve pain, a dark viscous shadow rising between us, rising up through the open window and into the night. We played a Schubert duet together. The sun didn’t hurt my skin anymore and we drove to Venice Beach in her Firebird, we drove down Sunset Boulevard singing along to Motörhead and Judas Priest on the radio.

Later we would go to Silver Lake and take turns photographing each other, and I would watch as she processed the pictures on her laptop, making subtle adjustments in color and contrast until I could admit I didn’t look ugly. We would lay on the floor and chainsmoke and watch Kenneth Anger movies projected onto the ceiling. Later I would meet her friends, give tarot readings to avante-garde artists on their honeymoon and get fish tacos with musicians I listened to in high school. I’d meet a real LA witch and go bar-hopping with models. Later I’d go back to San Francisco, go back to school, fall in love, start making music again, drop out of school, fall in love again, get a tattoo, and perform my first show. I’d see Marylene once more, in Joshua Tree, and then fall out of touch. All that would happen later.

On that first night, I didn’t know what might come, but I knew the absence I haunted would no longer exist and I would be returned to the world by the act of being seen. In my last moments of non-being, I watched the warm night air billow through the curtains, and I waited for Marylene to come home.

Marylene and I had met in June, sometime between midnight and six AM in a Berlin techno club. Nick knew her boyfriend Andrew from Brooklyn, and as they caught up we connected over our love of music, from Stravinsky to musique concrète to Delta blues. Marylene was wearing a sheer black shirt and dark eyeliner. She spoke with an emphatic French cadence, smoked Gauloises with casual grace, and wore her blonde hair long and slightly tangled. We had both just taken acid, I for the first time.

My relationship with Nick was new, and I was new to his world, the world of psychedelics and art and money, of Bushwick warehouse raves and summer techno pilgrimages to Berlin. I still carried both the moldy vulgarity of my West Virginian upbringing and a deep sense of my own misshapenness from growing up non-white and isolated by homeschool. I was afraid to open my mouth around his friends, afraid of being too sure of my own opinions, but as I talked to Marylene and the acid began its work I let myself think I could belong. In the haze and pounding bass, I imagined infinite pathways branching out from that moment, each transforming me into a different and glittering self: a musician, a writer, an artist, thin and sophisticated and worthy of love.

Perhaps that was why, over the next few months, I missed the signs that things weren’t working out with Nick. I had little experience with relationships, and had thought the tumultuous course of our four-month relationship might continue just as it was. I had thought, with no evidence, that he and I were both going to swallow our doubt and restlessness, and move in together in two days when my latest sublet, a flea-infested San Francisco apartment I shared with two DJs and a coke dealer, was over. When we broke up I had nowhere to go, no plans for the future, no school or employment to anchor me. I peddled my tragedy of abandonment on social media, looking for friends willing to store my belongings or provide a place to crash, no small sacrifice in a city where no one I knew could afford a living room. There, I saw Marylene’s post in search of a cat sitter.

We’d only met once, but I’d seen enough of her life on social media to envy her. She was a fashion photographer, and I had acne. She owned a black ‘77 Firebird, and I had never learned to drive. She toured with Japanese psych-rock bands, and I had only ever been a face in the crowd. She was a connection to Nick, and I was an episode in his past.

The next day, I cried on BART, the plane, the airport shuttle. By the time I arrived at the Villa Elaine apartments in Hollywood, I was dehydrated and dissociated. A four digit code took me through the black iron gates and into a courtyard with stone fountains and banana palms. It felt surreal: the colors too bright, the edges of things too sharp, the stillness and quiet and lushness too hermetic. Marylene’s neighbor Joyce gave me the keys, pointed out the units where Man Ray, Orson Welles, and Frank Sinatra once lived. She invited me over for tea sometime. Her warmth overwhelmed me; I made my excuses quickly and retreated.

Marylene’s loft had high ceilings and dark red floors. The cavernous atrium held a couch, a piano, and a shelf with synthesizers and a skull. Small steps led to a spare kitchen, which opened into a vertiginously long and narrow alleyway crammed with potted succulents and cigarette butts. A winding staircase led up into an alcove with a modest bed and bath. The cats, Grey and Glenn, followed me from room to room but kept a polite distance.

It felt like an interstitial place, a place disconnected from the narrative of my life thus far, from the world I knew, from my habits and comforts; any pain brought into it would remain frozen in time, unable to change or leave. I drew layers of gauzy curtains across the floor-length picture windows and locked myself in. I didn’t know it was possible to feel so alone.

On that first night, I unpacked. I had brought only a few changes of clothing, a tarot deck, my journal, and 20 hits of acid. I fed Marylene’s cats and picked at the food in Marylene’s fridge and lay restlessly in Marylene’s bed until it began to get light outside. I stayed in bed while the midday sun pierced through the curtains with angry heat. Faintly, I heard life outside continuing, and it seemed healthy and bright and horrible: fragments of Top 40 music from cars driving down Vine, fragments of conversation from people walking by, always fragments moving past me in my stillness. I wondered which side of the bed Marylene slept on, if she got up early or late, if Nick was in love with her, if she had a middle name. Eventually, it started to get dark again. I stayed in bed.

When I woke up again, I had become a non-being, existing only in the space left by the absence of a woman I barely knew. I sat in the bathtub and sampled the deep ambers of Marylene’s perfumes. I touched the austere white silk hanging in her closet and wondered if anything that elegant could work on me. As I folded and put away the clothes she’d left in the dryer I noted the brands, imagined wearing them, looking beautiful in them, being desired in them.

I fed her cats with precise scoops twice a day and played with them seriously and assiduously. I looked through her records, but didn’t listen to any because I was afraid to touch her intimidating mixer, afraid I’d damage her speakers by powering things on in the wrong order or plugging something in the wrong way. I didn’t play her piano because I didn’t want anyone to hear me. I put things back carefully when I used them.

One night I went outside. I walked to Sunset Boulevard to buy the toiletries I’d forgotten to pack, and came back with a box of nitrous and a bottle of wine. I finished both, watching the dark walls melt and breathe, watching skulls swim in and out of darkness. Inertia expanded inside me like nitrous, carrying blue numbness to my brain, to my heart, to the tips of my fingers. The next night I finished another box of nitrous and another bottle of wine. The next night, it became routine. In those seconds after a hit of nitrous I could plausibly conjure grandiose visions of reconciliation, forgiveness, and commitment. Sober, there was only an erased tape where once I had played and replayed my future with Nick: reading the books he liked, meeting the friends he talked about, DJing together in crowded Brooklyn warehouses and sweaty Berlin clubs.

Marylene texted me to check in, and met my honesty with her own. She’d flown to Brooklyn to save her relationship with Andrew, but she said everything she tried made it seem to fall apart faster. I blended her words with mine and wrote them in my journal. How can something become nothing? Where does the potential go? What happens to the space where it once was? I had no wisdom or reassurance to share, so I sent photographs of her cats, of shadows on the floor, of a tongue of cigarette smoke curling upward in still air, trying to prove to her in an oblique visual language that she had been heard and understood. I knew little of Marylene’s personality, her behavior, the way she moved through the world, but I knew our pain oscillated at the same frequency; we resonated.

Marylene was the only person I was in regular contact with. I went out only at night to buy supplies, and when I talked to the cats my voice was whispery with disuse. When the cashier at the nitrous shop told me I should be taking B vitamins to prevent nerve damage, I started going somewhere else. When Joyce knocked, I hid from her. I watched as texts from worried friends in San Francisco piled up, then as my phone rang and rang and rang. Instead of reaching out, I gave the cats tarot readings. I went through the deck and picked out the swords, explaining exactly what flavor of pain each embodies, and then I pulled cards to represent what in their lives was hurting. The ten of cups suggests you are unhappy because you avoid connection, the Sun here indicates your lack of successes in life. They walked across the spread to come twine themselves around me with what I couldn’t convince myself was real affection.

Something like a week passed, but time did not find me in Marylene’s apartment: the fruit I bought had not ripened, the emails I tried to write went unsent, and my pain had not diminished or shifted. One night I took the acid, trying to remember what it was like to feel the raw manifold potential of life. Instead, I felt I had lost control over my one bleak and clouded fate. My journaling shifted to third person. I wrote demonically, as if everything I had ever seen or thought became sentient and fought to escape my dying body. I became certain I would take my own life, without even wanting to, because I didn’t know where, or how, I was going to live after this. I could see no future beyond my stay at Marylene’s.

I drafted notes to Marylene, to explain myself: “Thank you for letting me stay in your beautiful home. The cats have been fed once today. My body is in the bedroom…” I wondered if Marylene ever sat at the kitchen table, smoking and waiting to die. If even someone like Marylene couldn’t find bliss in love, then what hope was there for me?

One night Marylene texted that she and Andrew were over. I turned out all the lights and texted back a picture of the unbroken darkness. She promised that I could stay as long as I needed to.

I imagined that Marylene came back and I gave her my journal to read. We put lit candles on every flat surface and sat on the floor with the cats in a circle of salt and ash and cast a spell to dissolve pain, a dark viscous shadow rising between us, rising up through the open window and into the night. We played a Schubert duet together. The sun didn’t hurt my skin anymore and we drove to Venice Beach in her Firebird, we drove down Sunset Boulevard singing along to Motörhead and Judas Priest on the radio.

Later we would go to Silver Lake and take turns photographing each other, and I would watch as she processed the pictures on her laptop, making subtle adjustments in color and contrast until I could admit I didn’t look ugly. We would lay on the floor and chainsmoke and watch Kenneth Anger movies projected onto the ceiling. Later I would meet her friends, give tarot readings to avante-garde artists on their honeymoon and get fish tacos with musicians I listened to in high school. I’d meet a real LA witch and go bar-hopping with models. Later I’d go back to San Francisco, go back to school, fall in love, start making music again, drop out of school, fall in love again, get a tattoo, and perform my first show. I’d see Marylene once more, in Joshua Tree, and then fall out of touch. All that would happen later.

On that first night, I didn’t know what might come, but I knew the absence I haunted would no longer exist and I would be returned to the world by the act of being seen. In my last moments of non-being, I watched the warm night air billow through the curtains, and I waited for Marylene to come home.

|

LeeAnn Perry is a scientist, musician, and A/V artist based in San Francisco. She can be found at lnpry.space. Photo credit: Marylene.

|