Overlooking Honey Lake from the Diamond Range

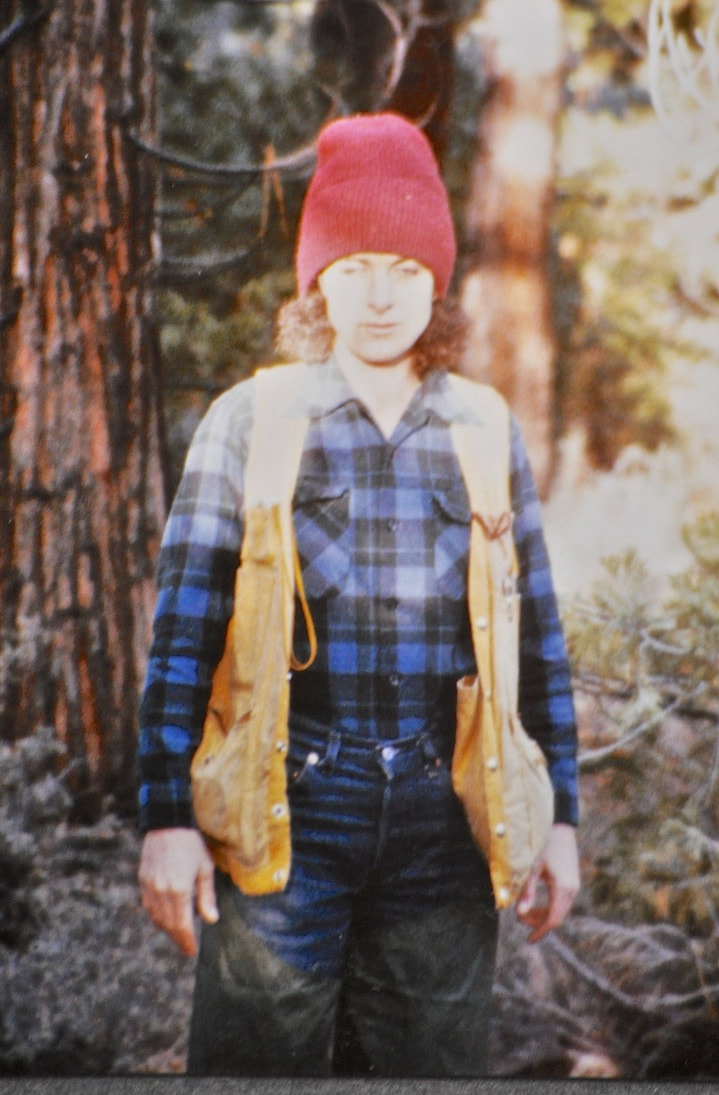

By Martha S. Mitchell

April 15, 2024

April 15, 2024

In its far north, California’s Sierra Nevada breaks into three massive ranges, a region guarded by fierce roads, wild rivers, and rocky ridges. Diamond Range is the easternmost. It combs moisture out of winds pushing inland from the Pacific, so it’s dry on this last escarpment of the northern Sierra. A vast rain shadow stretches over the high desert from the foot of the Diamond Range eastward to the horizon and beyond.

I’m hanging flags on a raveling granite slope here to determine the location of a timber harvest road. From my perch on a boulder clinging to the escarpment thousands of feet above the high desert, I peer down at Honey Lake. It seems to have come unmoored from its basin and floats in the shimmering air of distance. Neat green fields of alfalfa encircle the alkali flats that rim the grey-brown plane of the shrunken lake, whose waters boats sometimes crossed. On the far horizon stands the first upthrust ridge system of the Basin and Range, the Fort Sage Mountains.

Meltwaters from waning glaciers once filled the basin below, creating an inland lake. Shelf-like terraces low on the surrounding ridges tell of wind-driven waves that once rushed to shore. A lush riparian fringe offered a stopping-over place for migrating waterfowl, and a bountiful home for the Northern Paiute people.

But that long era has passed. Relentless evaporation has diminished Honey Lake’s depth and surface area. The shrinking waters have grown increasingly saline. Salt flats encircle the shrunken water body. Now it’s so shallow that the unfettered fetch of desert wind kicks up waves that stir the muddy bottom, creating a dirty opaque soup.

Loose, decomposed granite shifts beneath every step as I traverse the sheer slope. The ground rolls over so steeply that it’s hard to keep my footing. I scramble up and back, scouting keyhole turn-arounds, landings, draw crossings, switchbacks and easy grades for the haul road. The Jeffrey pines here are ancient, gorgeous, and the wind sings in their crowns.

I'm delighted to be working in these woods. Walking through this stand of virgin timber is perhaps one of the greatest joys I may know in my lifetime¾the delight of communing with light, time, and staggering beauty among ancient trees that have withstood centuries, like something mystical and divine.

But I suffer a nagging remorse. Above, in the canopy, birds I can't see shriek and whisper about a two-legged creature afoot in this most remote place—a human being marking the alignment for a dirt road. The road will bring the lowboy and dozer, the fallers, the cables for the spar tree and the choker setters, the yarder, the loader and the log trucks that will deliver freights of thick-boled, thirty-two-foot logs to the mill. I’m burdened with remorse about this harvest unit, but blessed to be in the presence of its magnificence.

When I work alone, I surrender to the mystery of the woods and their wonders. I’m ensnared by the awesome splendor of unmolested forests. I’m subject to rapture, melancholy, flights of spiritual fancy, and deep thoughts. The trees get a hold of me. I’m smitten by small beauties and mesmerized by the shifting light filtering through the canopy. The complexity of mountains and woodlands, and the webs of life they hold make me humble. At the end of my work days, I return to the Forest Service yard at a loss for words, lurching in my boots from miles of side-hill walking in ancient stands of timber. My boss gives me a knowing nod. “God’s country,” he remarks, knowing well the grand sweep of the Diamond Range country. For all his lifetime of proud logging, I know he feels smitten in the same way.

I rarely think about this when I work with a partner. We shout back and forth on the trial route of the road, talking a spicy jargon in a boastful drawl tinged with bravado. Hey there! Got’cher rag tape? Okay, climb this baby like a big dog! Put’er in granny gear and gun her good! I’ll run grade. Hup! Take’er to the top! Whoa now! That’s seven hundred feet at twenty percent. No way, Jose. We’re in switchback country now. . .

Today, I’m worrying about the trees. These colossal Jeffrey pines are wider in girth than a tall man’s outstretched arms. They’ve witnessed five centuries of wind, fire, disease, and a slowly drying climate. It’s incredibly arid here in the eastern lee of the moisture-wringing ranges. Perhaps the trees’ reaching roots are able to tap water deep in cracks of the granite bedrock. Maybe they’re finding water where gravity pulls it down through the soil to the footslopes of the range. Foresters know these conifers need at least sixteen inches of moisture a year to thrive. Yet I’ve worked in areas of the northeastern Sierra that receive far less precipitation, but observed ancient stands of Jeffrey pine enduring. Perhaps they’re relict from wetter times.

But what about the seedlings the hoe-dads will stab into the ground after the old trees are harvested? Will there be enough moisture in the thin covering of decomposed granite for them to survive? Shame rises in the back of my neck in this incredible place of beauty and perseverance. After this stand is gone, perhaps the seedlings won’t thrive and an entire ecosystem will be lost.

It’s curious: I’ve pored over early topographic maps of the northern Sierra’s montane valleys, the green jewels of the mountains. Grabens, they call them¾the down-faulted troughs between the great uplifted ranges. The old maps label many of these valleys as swampland. In Red Clover Valley one can see where settlers and ranchers dug ditches, drained wet areas and relocated creeks and their tributaries to expand their pasturelands. But the eastside valleys that haven’t been dewatered look as if they’ve become dryer over time anyway. There is almost universal encroachment of juniper and sage into their former floodplains. If we are looking at post-Pleistocene drying—a gradual shrinking of lakes that once filled the grabens of the intermountain West—oughten’t we to be thinking about how to preserve the grand stands of trees that are relict from a wetter time?

I walk back to my rig and take the forest road down the escarpment’s steep stack of switchbacks, trailing a veil of dust as I descend to the high desert. The blacktop road skims green swards above Honey Lake where, like a pastoral painting, black angus cattle graze in wide pastures. At Hallelujah Junction, I turn west through Beckwourth Pass and along the edge of Sierra Valley’s marshes. Weary from a long day of hoofing sidehill on Diamond Mountain’s steep slope, I pull my green Forest Service rig into the gravel lot at the weathered Last Chance Saloon in Chilcoot, and park beside the mail delivery rig. Mornings and late afternoons, folks in this hard-working high desert country count on the pot of coffee the bartender keeps hot on the back bar all day.

I enter and take a seat at the bar a few stools away from the mail lady. Like people everywhere, we fall into conversation about the weather: this dry summer hard on the heels of a mild winter. She harks back to a wetter, colder time fifty years ago and more. Oh heck, she tells me, nudging her spectacles back up the bridge of her nose. Back when, September, deer-huntin’ time, the men tracked bucks in the snow. Yes ma’am, hereabouts. Nowadays we’re lucky to see snow by January, sometimes February. S’been a long time since we seen a white Christmas.

She considers her coffee mug and gives me a look that lets me know I’m about to be schooled in how it was. The mail lady continues, When I was a youngster here, snow fell so heavy one winter we had to leave the house by way of an upstairs window. Clumb straight out onto the roof. Had to tunnel out to the road. I shake my head to let her know I think it must have been mighty impressive. She continues, But that snowpack kept the house warm, I’ll tell you that. Like a blanket. Was a time every house, shed and barn hereabouts had a tin roof. Snow’d slip right off, you see. Folks stood boards and plywood sheets up against their sheds and whatnot to deflect the snow as it slid off, so it couldn’t shove structures off their foundations. But now, take a look at all the composition shingles. That’ll tell you somethin’. I tip my mug to drain the last drop and tilt my head toward the door. Pleasure, ma’am. Gotta get on back. Take her easy now.

On the long road back to the Forest Service compound, I muse that we have only the brief span of our own lifetimes to know anything about the climate in the run of a century or a millennium. This season I worked on the westernmost Claremont Range in an exceptionally cool and cloudy spring. Captivating scents swirled in the woods. Piney scents wafted on moist breezes. Afternoons brought the sweet stab of incense cedar and the perfume of sugar pines. I’d never seen such an abundance of wildflowers. The ground itself exhaled moisture in the warming days, and dry draws ran trickles late into August. It’s hard to know what his means in the context of climate over, say, five hundred years, or a thousand.

For a decade or so, I’ve watched the Sierra’s clean mountain skies fill with smoke each autumn as the Forest Service burns slash piles after logging. I’ve seen rain and snowmelt cause devastating losses of soils after broadcast burning consumes brush, ground cover, and the duff of centuries on the forest floor. I try to imagine the effects of logging and its aftermaths, forest by forest, in all the national and private forest lands of the country . . . the millions of acres of forest clearcuts and the bare slopes left behind. Imagine the dark, exposed soils absorbing heat in summer . . . all the mountains, all the world. Surely, lust for wood and the ecosystem changes logging has engendered have disturbed the reliable weather rhythms of each season.

Meteorologists describe a cell of high pressure in the Pacific that shifts north and south from year to year, according to vacillations in ocean temperatures. The high-pressure cell deflects moisture-laden westerly winds north and south as they approach the West Coast—sometimes sending storms north, clear to Vancouver, British Columbia, and sometimes south to Southern California. How does this pattern fit into long-term studies across centuries and millennia?

They say botanists examine pollen cores from the sediments of long-dried lakes to learn what plants flourished during historic climatic regimes. Dendrologists count ancient trees’ growth rings to figure out past weather. Anthropologists piece clues together to answer why entire civilizations abandoned regions that formerly supported them. These efforts tell of a watery world in flux. Seas rise. Their waters are locked up in polar ice. Glaciers claim the land, then melt, leaving rising seas and extensive lakes on the continents. With each change in climate over the vast extent of geologic time, entire associations of plants and animals advance, wane and disappear or are able to migrate to suitable environments.

These thoughts haunt me day after day as I continue locating roads among the last of the giant trees on Diamond Mountain. What solace the trees give. What utter holiness. What depth of understanding they yield to those who would wonder at their perseverance. I finish my work and at day’s end sit at the base of a grand Jeffrey Pine in awe of this primeval forest of giants from a former world. Grief clutches my chest. It’s time, I know, to forge a different path, a career I can assemble from wisdom hard-earned in the sweat of seasons I’ve worked in the Lost Sierra’s timberlands. I take a last look down at Honey Lake and make my way back to my rig. Centuries and millennia of needle-fall yield with a quiet softness at each step.

I’m hanging flags on a raveling granite slope here to determine the location of a timber harvest road. From my perch on a boulder clinging to the escarpment thousands of feet above the high desert, I peer down at Honey Lake. It seems to have come unmoored from its basin and floats in the shimmering air of distance. Neat green fields of alfalfa encircle the alkali flats that rim the grey-brown plane of the shrunken lake, whose waters boats sometimes crossed. On the far horizon stands the first upthrust ridge system of the Basin and Range, the Fort Sage Mountains.

Meltwaters from waning glaciers once filled the basin below, creating an inland lake. Shelf-like terraces low on the surrounding ridges tell of wind-driven waves that once rushed to shore. A lush riparian fringe offered a stopping-over place for migrating waterfowl, and a bountiful home for the Northern Paiute people.

But that long era has passed. Relentless evaporation has diminished Honey Lake’s depth and surface area. The shrinking waters have grown increasingly saline. Salt flats encircle the shrunken water body. Now it’s so shallow that the unfettered fetch of desert wind kicks up waves that stir the muddy bottom, creating a dirty opaque soup.

Loose, decomposed granite shifts beneath every step as I traverse the sheer slope. The ground rolls over so steeply that it’s hard to keep my footing. I scramble up and back, scouting keyhole turn-arounds, landings, draw crossings, switchbacks and easy grades for the haul road. The Jeffrey pines here are ancient, gorgeous, and the wind sings in their crowns.

I'm delighted to be working in these woods. Walking through this stand of virgin timber is perhaps one of the greatest joys I may know in my lifetime¾the delight of communing with light, time, and staggering beauty among ancient trees that have withstood centuries, like something mystical and divine.

But I suffer a nagging remorse. Above, in the canopy, birds I can't see shriek and whisper about a two-legged creature afoot in this most remote place—a human being marking the alignment for a dirt road. The road will bring the lowboy and dozer, the fallers, the cables for the spar tree and the choker setters, the yarder, the loader and the log trucks that will deliver freights of thick-boled, thirty-two-foot logs to the mill. I’m burdened with remorse about this harvest unit, but blessed to be in the presence of its magnificence.

When I work alone, I surrender to the mystery of the woods and their wonders. I’m ensnared by the awesome splendor of unmolested forests. I’m subject to rapture, melancholy, flights of spiritual fancy, and deep thoughts. The trees get a hold of me. I’m smitten by small beauties and mesmerized by the shifting light filtering through the canopy. The complexity of mountains and woodlands, and the webs of life they hold make me humble. At the end of my work days, I return to the Forest Service yard at a loss for words, lurching in my boots from miles of side-hill walking in ancient stands of timber. My boss gives me a knowing nod. “God’s country,” he remarks, knowing well the grand sweep of the Diamond Range country. For all his lifetime of proud logging, I know he feels smitten in the same way.

I rarely think about this when I work with a partner. We shout back and forth on the trial route of the road, talking a spicy jargon in a boastful drawl tinged with bravado. Hey there! Got’cher rag tape? Okay, climb this baby like a big dog! Put’er in granny gear and gun her good! I’ll run grade. Hup! Take’er to the top! Whoa now! That’s seven hundred feet at twenty percent. No way, Jose. We’re in switchback country now. . .

Today, I’m worrying about the trees. These colossal Jeffrey pines are wider in girth than a tall man’s outstretched arms. They’ve witnessed five centuries of wind, fire, disease, and a slowly drying climate. It’s incredibly arid here in the eastern lee of the moisture-wringing ranges. Perhaps the trees’ reaching roots are able to tap water deep in cracks of the granite bedrock. Maybe they’re finding water where gravity pulls it down through the soil to the footslopes of the range. Foresters know these conifers need at least sixteen inches of moisture a year to thrive. Yet I’ve worked in areas of the northeastern Sierra that receive far less precipitation, but observed ancient stands of Jeffrey pine enduring. Perhaps they’re relict from wetter times.

But what about the seedlings the hoe-dads will stab into the ground after the old trees are harvested? Will there be enough moisture in the thin covering of decomposed granite for them to survive? Shame rises in the back of my neck in this incredible place of beauty and perseverance. After this stand is gone, perhaps the seedlings won’t thrive and an entire ecosystem will be lost.

It’s curious: I’ve pored over early topographic maps of the northern Sierra’s montane valleys, the green jewels of the mountains. Grabens, they call them¾the down-faulted troughs between the great uplifted ranges. The old maps label many of these valleys as swampland. In Red Clover Valley one can see where settlers and ranchers dug ditches, drained wet areas and relocated creeks and their tributaries to expand their pasturelands. But the eastside valleys that haven’t been dewatered look as if they’ve become dryer over time anyway. There is almost universal encroachment of juniper and sage into their former floodplains. If we are looking at post-Pleistocene drying—a gradual shrinking of lakes that once filled the grabens of the intermountain West—oughten’t we to be thinking about how to preserve the grand stands of trees that are relict from a wetter time?

I walk back to my rig and take the forest road down the escarpment’s steep stack of switchbacks, trailing a veil of dust as I descend to the high desert. The blacktop road skims green swards above Honey Lake where, like a pastoral painting, black angus cattle graze in wide pastures. At Hallelujah Junction, I turn west through Beckwourth Pass and along the edge of Sierra Valley’s marshes. Weary from a long day of hoofing sidehill on Diamond Mountain’s steep slope, I pull my green Forest Service rig into the gravel lot at the weathered Last Chance Saloon in Chilcoot, and park beside the mail delivery rig. Mornings and late afternoons, folks in this hard-working high desert country count on the pot of coffee the bartender keeps hot on the back bar all day.

I enter and take a seat at the bar a few stools away from the mail lady. Like people everywhere, we fall into conversation about the weather: this dry summer hard on the heels of a mild winter. She harks back to a wetter, colder time fifty years ago and more. Oh heck, she tells me, nudging her spectacles back up the bridge of her nose. Back when, September, deer-huntin’ time, the men tracked bucks in the snow. Yes ma’am, hereabouts. Nowadays we’re lucky to see snow by January, sometimes February. S’been a long time since we seen a white Christmas.

She considers her coffee mug and gives me a look that lets me know I’m about to be schooled in how it was. The mail lady continues, When I was a youngster here, snow fell so heavy one winter we had to leave the house by way of an upstairs window. Clumb straight out onto the roof. Had to tunnel out to the road. I shake my head to let her know I think it must have been mighty impressive. She continues, But that snowpack kept the house warm, I’ll tell you that. Like a blanket. Was a time every house, shed and barn hereabouts had a tin roof. Snow’d slip right off, you see. Folks stood boards and plywood sheets up against their sheds and whatnot to deflect the snow as it slid off, so it couldn’t shove structures off their foundations. But now, take a look at all the composition shingles. That’ll tell you somethin’. I tip my mug to drain the last drop and tilt my head toward the door. Pleasure, ma’am. Gotta get on back. Take her easy now.

On the long road back to the Forest Service compound, I muse that we have only the brief span of our own lifetimes to know anything about the climate in the run of a century or a millennium. This season I worked on the westernmost Claremont Range in an exceptionally cool and cloudy spring. Captivating scents swirled in the woods. Piney scents wafted on moist breezes. Afternoons brought the sweet stab of incense cedar and the perfume of sugar pines. I’d never seen such an abundance of wildflowers. The ground itself exhaled moisture in the warming days, and dry draws ran trickles late into August. It’s hard to know what his means in the context of climate over, say, five hundred years, or a thousand.

For a decade or so, I’ve watched the Sierra’s clean mountain skies fill with smoke each autumn as the Forest Service burns slash piles after logging. I’ve seen rain and snowmelt cause devastating losses of soils after broadcast burning consumes brush, ground cover, and the duff of centuries on the forest floor. I try to imagine the effects of logging and its aftermaths, forest by forest, in all the national and private forest lands of the country . . . the millions of acres of forest clearcuts and the bare slopes left behind. Imagine the dark, exposed soils absorbing heat in summer . . . all the mountains, all the world. Surely, lust for wood and the ecosystem changes logging has engendered have disturbed the reliable weather rhythms of each season.

Meteorologists describe a cell of high pressure in the Pacific that shifts north and south from year to year, according to vacillations in ocean temperatures. The high-pressure cell deflects moisture-laden westerly winds north and south as they approach the West Coast—sometimes sending storms north, clear to Vancouver, British Columbia, and sometimes south to Southern California. How does this pattern fit into long-term studies across centuries and millennia?

They say botanists examine pollen cores from the sediments of long-dried lakes to learn what plants flourished during historic climatic regimes. Dendrologists count ancient trees’ growth rings to figure out past weather. Anthropologists piece clues together to answer why entire civilizations abandoned regions that formerly supported them. These efforts tell of a watery world in flux. Seas rise. Their waters are locked up in polar ice. Glaciers claim the land, then melt, leaving rising seas and extensive lakes on the continents. With each change in climate over the vast extent of geologic time, entire associations of plants and animals advance, wane and disappear or are able to migrate to suitable environments.

These thoughts haunt me day after day as I continue locating roads among the last of the giant trees on Diamond Mountain. What solace the trees give. What utter holiness. What depth of understanding they yield to those who would wonder at their perseverance. I finish my work and at day’s end sit at the base of a grand Jeffrey Pine in awe of this primeval forest of giants from a former world. Grief clutches my chest. It’s time, I know, to forge a different path, a career I can assemble from wisdom hard-earned in the sweat of seasons I’ve worked in the Lost Sierra’s timberlands. I take a last look down at Honey Lake and make my way back to my rig. Centuries and millennia of needle-fall yield with a quiet softness at each step.

|

Martha S. Mitchell is a physical geographer and natural science writer. At age twenty, inspired by the wilderness writings of Gary Snyder, she decided to leave the San Francisco Bay area for life and work in California’s remote northern Sierra Nevada. Field work in the big timber offered adventure, enormous physical challenges, and heart-stopping, mythical beauty. Yet, as her understanding of forest ecosystems deepened and she observed the ravages of old-growth logging, she increasingly felt burdened that her work was contributing to the death of what she most loved.

After earning a master’s degree specializing in geomorphology--the study of factors shaping the landscape--she went on to work in water and natural resource protection. Mitchell’s technical-professional work is widely published in Oregon and in the international journal of professionals in erosion & sediment control. She is also a poet and musician. “Overlooking Honey Lake from the Diamond Range” is excerpted from her creative nonfiction book-in-progress, The Lost Sierra. Author's Note:I’m grateful to have found Heimat as a home for my deeply place-based prose, and its readers thirsty for lyrical nature writing. |