Theo, Stuck in Twine

By Kasey Butcher Santana

April 15, 2023

April 15, 2023

Theodora stood alone, panic in her big, dark eyes. When she looked at me, she made the guttural clucking sound that stressed or annoyed alpacas use. I walked toward her, greeting her cheerfully until I saw the twist of twine around her throat. I froze, seeing myself reflected in her anxious eyes.

Alpacas need other alpacas. Being without a companion stresses them out so much that some people say they can die of loneliness. It was unusual to see Theodora by herself when I went to take the chickens a half-eaten apple, leftover from my toddler’s breakfast. As I entered the pasture, looking at Theo standing by the feeder that my husband, Julio, built out of pallets, and saw a length of twine around her neck, I understood—in a startling instant—how much trouble she was in.

We feed the alpacas from bales of hay held together by twine on either end. If we remove the ties immediately upon putting a new bale in the feeder, the herd spills hay everywhere. Hay is expensive, so we experimented with leaving the twine on until it grew slack, then removing it, but that posed the risk of one of the herd getting caught in it first. With their long, graceful necks, strangulation is one of the hazards alpacas face. When I saw Theo, I knew what must have happened. The twine both caught around her neck and stuck on one of the feeder’s joints. I was surprised that all of the other girls left her alone when they sought fresher hay behind the barn.

First, I reached for the twine, but Theodora rebuffed me, huffing angry, hay-scented breaths and jerking her chin to warn me that she was going to spit. I needed scissors to free her quickly. The box cutter in the barn was missing, so I ran to the kitchen and grabbed the shears.

The twine wrapped tightly around her throat and double looped while the feeder acted as a garrote. I had to avoid further alarming Theo, causing her to choke herself while resisting me. Alpacas tend to avoid being touched, even when in distress. As I tried again to reach for the twine, Theo spat in my face, covering my glasses with pungent bits of regurgitated hay and stomach bile. She tilted her chin, craning her neck back in an impossible-looking arch so she could spit at me where I stood behind her. Gagging, I calmly placed my shoulder behind her neck, bracing her head with the top of my own and avoiding her hind legs so she could not kick me. I wrapped one arm around her throat and held on. With Theo in the gentlest version of a headlock, I cut the twine.

No longer tethered to the feeder, Theo still had coarse polyester fibers around her throat and snagged in her soft fleece. Pressing my body to her, trying to soothe her, I teased the twine away from her coat and put it in my pocket. Underneath all that fluff, her skin was unbroken. Hushing her like a baby, I stroked her neck, and she calmed. “I’m sorry, Theodora. I’m so, so sorry,” I told her over and over.

When I released her, instead of spitting at me again, she gave me a long look and then went to join her herdmates, who had returned to the pasture to watch her ordeal. Keeping my distance, I followed them back to the hay pile, hoping to see Theo eat and drink before I left her alone.

Once I knew that she was uninjured, I went inside to wash the nauseating smell of spit off my glasses, face, hair, and mouth. The earthy, sickly aroma lingers. In the shower, I sobbed, imagining what could have happened if I did not find Theo in time. How could we live with ourselves if she had strangled herself or broken her neck after getting caught in the twine? Death is part of caring for animals—part of life—but to lose an alpaca for such a preventable, torturous reason would have felt crushing, to us and the rest of the herd.

We often wonder about how our alpacas’ inner lives. They are intelligent and curious, often coming to meet us at the fence when we go out to the pasture, but they are more invested in their herd than in us. Our dinner table looks out into their enclosure, and sometimes we catch them watching us, but we are an afterthought, a curiosity—the creatures who bring them hay. Do they trust us? Do they like us? The alpacas are not our friends. We farm them, but they really belong to each other. Theodora's best friend, Clementine, comes closest to showing us affection, approaching me with a toothy grin and nuzzling noses each time we meet. If I get busy and forget to greet her, she follows me until I pay attention to her. The rest prefer us a few feet away. After her misadventure with the twine, I wondered how Theodora felt. How did she understand what happened? To her, did I save the day, or put her life in danger, or some mixture of the two, setting a fire just to put it out?

I requested to secure the alpacas in the barn that night, a chore Julio usually does. I wanted to see Theodora again, so she would not associate me with her terrifying experience. At the sound of the lid lifting off the metal trash can that houses their evening treat, the girls came running to the barn with Theo bringing up the rear. As she stepped inside, she brushed past my legs, then turned to watch me carefully. Alpacas have strong memories, a survival skill for foragers who are also prey animals in the wild. What she was expressing with her big, serious eyes, I do not know, but she did not spit at me, so we were in good enough standing. In the quiet of the barn, I waited for her to communicate the alpaca way—neutral ears and a steady gaze, her strong body relaxed. I held out a handful of pellets, and she ate greedily. I was still a trusted source of food, and she was okay.

Alpacas need other alpacas. Being without a companion stresses them out so much that some people say they can die of loneliness. It was unusual to see Theodora by herself when I went to take the chickens a half-eaten apple, leftover from my toddler’s breakfast. As I entered the pasture, looking at Theo standing by the feeder that my husband, Julio, built out of pallets, and saw a length of twine around her neck, I understood—in a startling instant—how much trouble she was in.

We feed the alpacas from bales of hay held together by twine on either end. If we remove the ties immediately upon putting a new bale in the feeder, the herd spills hay everywhere. Hay is expensive, so we experimented with leaving the twine on until it grew slack, then removing it, but that posed the risk of one of the herd getting caught in it first. With their long, graceful necks, strangulation is one of the hazards alpacas face. When I saw Theo, I knew what must have happened. The twine both caught around her neck and stuck on one of the feeder’s joints. I was surprised that all of the other girls left her alone when they sought fresher hay behind the barn.

First, I reached for the twine, but Theodora rebuffed me, huffing angry, hay-scented breaths and jerking her chin to warn me that she was going to spit. I needed scissors to free her quickly. The box cutter in the barn was missing, so I ran to the kitchen and grabbed the shears.

The twine wrapped tightly around her throat and double looped while the feeder acted as a garrote. I had to avoid further alarming Theo, causing her to choke herself while resisting me. Alpacas tend to avoid being touched, even when in distress. As I tried again to reach for the twine, Theo spat in my face, covering my glasses with pungent bits of regurgitated hay and stomach bile. She tilted her chin, craning her neck back in an impossible-looking arch so she could spit at me where I stood behind her. Gagging, I calmly placed my shoulder behind her neck, bracing her head with the top of my own and avoiding her hind legs so she could not kick me. I wrapped one arm around her throat and held on. With Theo in the gentlest version of a headlock, I cut the twine.

No longer tethered to the feeder, Theo still had coarse polyester fibers around her throat and snagged in her soft fleece. Pressing my body to her, trying to soothe her, I teased the twine away from her coat and put it in my pocket. Underneath all that fluff, her skin was unbroken. Hushing her like a baby, I stroked her neck, and she calmed. “I’m sorry, Theodora. I’m so, so sorry,” I told her over and over.

When I released her, instead of spitting at me again, she gave me a long look and then went to join her herdmates, who had returned to the pasture to watch her ordeal. Keeping my distance, I followed them back to the hay pile, hoping to see Theo eat and drink before I left her alone.

Once I knew that she was uninjured, I went inside to wash the nauseating smell of spit off my glasses, face, hair, and mouth. The earthy, sickly aroma lingers. In the shower, I sobbed, imagining what could have happened if I did not find Theo in time. How could we live with ourselves if she had strangled herself or broken her neck after getting caught in the twine? Death is part of caring for animals—part of life—but to lose an alpaca for such a preventable, torturous reason would have felt crushing, to us and the rest of the herd.

We often wonder about how our alpacas’ inner lives. They are intelligent and curious, often coming to meet us at the fence when we go out to the pasture, but they are more invested in their herd than in us. Our dinner table looks out into their enclosure, and sometimes we catch them watching us, but we are an afterthought, a curiosity—the creatures who bring them hay. Do they trust us? Do they like us? The alpacas are not our friends. We farm them, but they really belong to each other. Theodora's best friend, Clementine, comes closest to showing us affection, approaching me with a toothy grin and nuzzling noses each time we meet. If I get busy and forget to greet her, she follows me until I pay attention to her. The rest prefer us a few feet away. After her misadventure with the twine, I wondered how Theodora felt. How did she understand what happened? To her, did I save the day, or put her life in danger, or some mixture of the two, setting a fire just to put it out?

I requested to secure the alpacas in the barn that night, a chore Julio usually does. I wanted to see Theodora again, so she would not associate me with her terrifying experience. At the sound of the lid lifting off the metal trash can that houses their evening treat, the girls came running to the barn with Theo bringing up the rear. As she stepped inside, she brushed past my legs, then turned to watch me carefully. Alpacas have strong memories, a survival skill for foragers who are also prey animals in the wild. What she was expressing with her big, serious eyes, I do not know, but she did not spit at me, so we were in good enough standing. In the quiet of the barn, I waited for her to communicate the alpaca way—neutral ears and a steady gaze, her strong body relaxed. I held out a handful of pellets, and she ate greedily. I was still a trusted source of food, and she was okay.

|

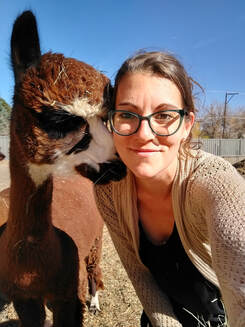

Kasey Butcher Santana (she/her) is co-owner/operator of Sol Homestead, a backyard alpaca farm where she and her husband also raise chickens, bees, pumpkins, and their daughter. When not beekeeping or gardening, she loves to read mystery novels and hike. Kasey earned a Ph.D. in American literature from Miami University and has worked as an English teacher and a jail librarian. Recently, her work has been published in Geez Magazine, The Hopper, Canary, and Farmer-ish. She chronicles life at the homestead on Instagram @solhomestead.

|